…and Other MisAdventures in Attachment Injury and Trauma Response.

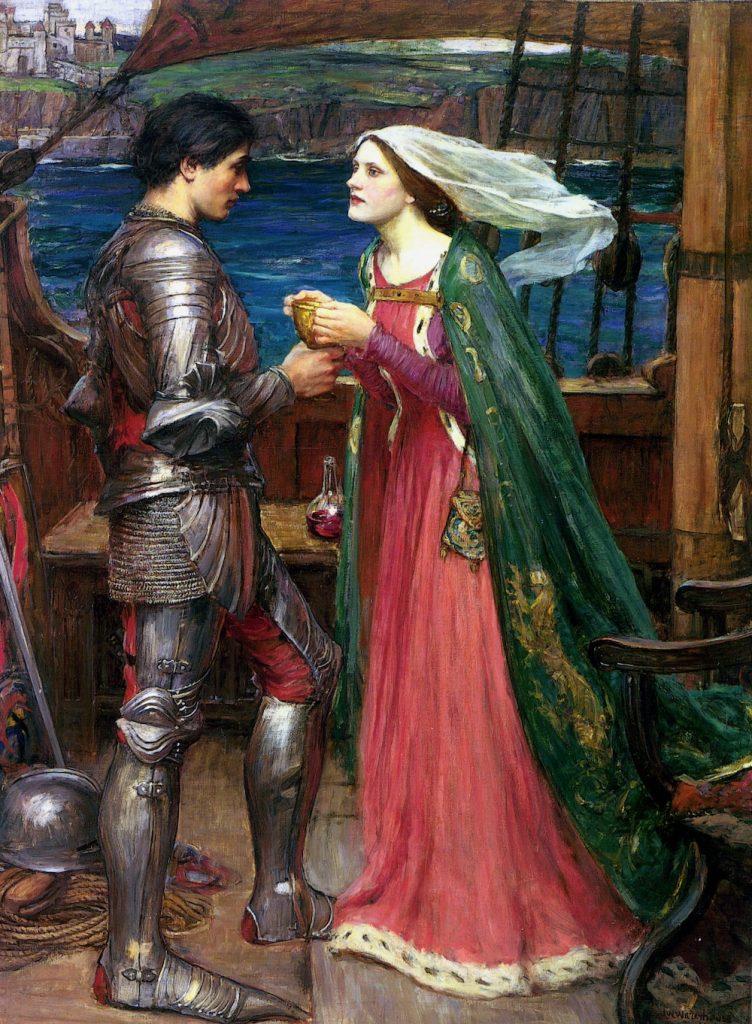

Tristan and Isolde with the Potion (1916) by John William Waterhouse

Public Domain. Cropped from original via Wikimedia Commons

Content note: This essay discusses trauma, childhood neglect & abuse, fawning, dissociation, neurodivergence, sex, and—gasp—Pre-Raphaelite art.

Have you ever heard of limerence? I hadn’t until very recently. I only know what it is now because my buddy Brad asked if I was familiar with the concept. We were discussing our current dating woes, and I think he brought it up to illustrate a point about his own situation. Although after the fact, I realized he was also insinuating something about mine. He’s familiar enough with my family story and a solid portion of my relationship history, and he is smart enough to make an educated guess. He had us both pegged. In any case, while texting my old friend, I performed a preliminary Google search. It only took about sixty seconds to understand what limerence is and burst right into tears.

Limerence. Well, fuck.

For those unfamiliar, the term limerence was coined in the 1970s by psychologist Dorothy Tennov. She wrote a book called Love and Limerence in which she used her made-up term to describe involuntary romantic fixation. This is not the excitement of a crush, nor the rush and joy of new love. It’s an intense and uncontrollable interest in a person, regardless of romantic reciprocation. In fact, limerence generally follows close on the heels of rejection or unrequited affection. When you read up on limerence, you will see these terms used over and over:

Infatuation. Obsession. Addiction.

These are words we enjoy using casually and often hyperbolically.

I’m addicted to Funyuns.

I’m infatuated with Bandit Healer.

I’m obsessed with my autistic special interest.

Okay, the last statement is not an exaggeration, but it carries little moral judgment or warning, unlike, for example, saying, “I am obsessed with my electrician.” Nobody wants to hear that. Especially not my electrician.

When we do hear ambiguous claims like this, we brace and hunt desperately for that hyperbole. Because when these words are used literally and in all seriousness, they tend to evoke unease, as if the person who is addicted, obsessed, or infatuated has careened across the median of the moral and rational interstate. We suspect they can’t be trusted and, in the worst cases, worry they might be capable of unfortunate behaviors.

Inherent in these statements is a loss of control. Limerence is sometimes defined as love addiction, but that’s not how I think of it or experience it. For me, limerence is a very primal reaction to an even more basic attachment injury. Scaled up to my adult brain, it’s a very savvy self-soothing technique that hijacks some of my neurotype’s more practiced habits, inclinations, and specialties. It’s a crazy-complex coping mechanism, and after it’s done comforting you, it can feel brutal in its relentlessness.

While in limerence, everything in my world points to the object of my desire. For the record, Tennov called this person one’s limerent object, and while I sort of bristle at that terminology, I must concede its accuracy. When someone becomes the focus of your limerence, you do indeed objectify them. Heavily. I faithfully, ruthlessly maintain a romance with the idea of my person—the parts of him that I find the most attractive, or even qualities that I create in stories about him. I can think of little else. Everything he touched, every way he touched me, everything we talked about, every novel situation and random occurrence brings him to mind. I wonder what he would think or how he might react. And in almost every spare moment, I review memories, tell myself tales, imagine exciting encounters, and envision endless satisfying outcomes. It feels like my default mode network becomes a full-time, fully automated limerence generator. It’s fucking bananas, and it’s exhausting.

If I were to accept the word “addiction” in association with limerence, it’s very much on a neurochemical level. Limerent daydreaming is as potent as any drug I have ever taken, and it is wicked hard to get under control. And in case I was not previously clear, this is not just me thinking of a crush wistfully from time to time. This is a well-established, hyperaroused pattern of compulsive thinking that is directly keyed into my brain’s reward and attachment system. I mean literally. I am not addicted to my electrician so much as to all the fucking glorious dopamine and oxytocin that flood my system when I think of him. I can’t overstate how necessary and out of control this can feel at the exact same time. I guess that’s a fair expression of a lot of addiction.

The magical thinking and storytelling of limerence allow us to feel certainty while enduring confusion and ambivalence, loved while icing the sting of rejection, and safety while mired in loss and disconnection. It’s your brain and nervous system on a rescue mission. It does precisely what any good trauma response tries to do: it wants to save us.

John William Waterhouse, Echo and Narcissus (1903).

Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.

I’ve been a limerent object twice, that I know of. On two separate occasions, individuals have approached me and made it clear that they had a relationship with me that I was not part of. Literally. I considered them acquaintances. They had no significant role in my life, but I loomed large in theirs. They had a relationship with the idea of me.

These were unsettling, out-of-the-blue encounters. In both cases, I was caught entirely unawares. I do not know what prior conversation, stolen moment, or misinterpreted moment might have triggered these two individuals to fall in love with the idea of me, but I now have a much greater appreciation of what must have been going on underneath their assumptions and proclamations—a deep need to be seen, validated, and loved. It was not about me; it was about them and what they needed.

At the time, I was so confused by and uncomfortable with their advances. In both instances, I managed to clumsily reject the stories they were telling themselves and me, and shut it all down. I was young and awkward and had not the slightest clue how to handle myself or others with genuine care. I am glad these encounters never crossed any significant boundaries or created any sense that I was unsafe. I wish I could say how these two people fared after my rejection, but I really don’t know. From my perspective, it was flustering and rough, but I also knew it could have been so much worse. I am sure limerence is the reason for so much difficult and even frightening behavior. And of course, people do do terrible things in the name of forsaken love. I’ll leave that here. I am not going to speak of this potential dark side of limerence, but I will share how limerence has shown up for me twice.

My first and worst experience with limerence was with a young man I was involved with when I was in my teens and early twenties—from my last year of high school, through my only year at university, to my first year living on my own in the city. He was a gorgeous, charismatic boy, self-styled poet, lead singer, head case, and I adored him. He treated me like shit. Which, of course, is awful, but looking back, I can’t imagine he had a single lover or friend who did not feel like he had browbeaten them with his ego and bad behavior. I am certain, too, that he was suffering a great deal. No one acts the way he did when they are right as rain. I did not have much of that perspective at the time, however. I just knew he was a tortured, yet gorgeous, boy who had shown me his attention and the tiniest sliver of his heart, and it felt like he was breathing life into me. I probably could have escaped relatively unscathed had he just fucked me a few times and dumped me, but that’s not what he did. He strung me along.

And here is the first clue that the particular flavor of heartache that triggers limerence in me is that of wanting, briefly having, then apparently being led on. From the initial glow of meeting him, through the terrible treatment, the on-again, off-again, the intensity, the exquisite attention, the fucking crazy sex, the distance, the proximity, the confusion, the excuses, the aloofness, the professions of love, the erratic communication, the crashing for days, the high-stakes rewards, the uplifting validation, the uncertainty of reciprocation, the risk of rejection, the everything-uncertain-all-the-time of him, I could not and would not look away. It triggered something staggering and uncontrollable in me.

Infatuation. Obsession. Addiction.

I couldn’t have him, so I couldn’t get enough of him. For almost three years, he came and went, and I pined after him. And, oh man, am I embarrassed by this—by what, at the time, I perceived as weakness and lack of self-respect. No one wants to be hung up on an unrequited love for that long. It speaks to one’s lack of strength and character. Or so I told myself.

Life went on. He vanished for good at some point, and over months and months, my limerence faded.

Fast forward almost 30 years. This time around, my would-be was kinder, gentler, and way more delightful (this was the wanting). It started with a brilliant, breathtaking intensity and a goddamn glorious series of encounters that left me feeling like I was waking from a long, middle-aged Sleeping Beauty-style slumber (this was the having). Then it stalled and shuddered to a confusing halt. He grew inconstant. His texts said one thing; his actions said another; his silences said a third, completely mystifying thing. Suddenly, I was savoring breadcrumbs. Uh oh. (This was the hook.)

And God bless me, I am mature and mindful enough that I saw much of it unfold in slow motion. Adult Mars was holding it down, managing her expectations, setting boundaries, being appropriately vulnerable, and self-respecting. If I were desperate for anything, it was some real, overdue relational work and healing. This was nothing I couldn’t handle, and handle happily. My good nature encouraged me to give him the benefit of the doubt, so long as I could continue to occasionally enjoy his company—or that is, as long as he still came over occasionally and screwed my brains out. I chose to take all his apologies and overly vague explanations at face value. What did I have to lose, I wondered to myself. But something about the unskillful way he pulled away snagged a tripwire in my psyche. You see, I missed what was happening three levels down in my subconscious and my nervous system. Even as I broke it off with him, it was too late. I was in it, and what came next wasn’t about a failed romance or even managing a breakup—it was a trauma response.

Because by then, in full-on Internal Family System terms, one or ten younger versions of me were freaking the fuck out. They could not even comprehend, let alone trust, any of the brave, self-actualized things I was attempting to do for myself now. All they knew was what we had endured before, when we had no maturity, agency, or healing to sustain us. They felt rejected, undervalued, lonely, scared, and unsafe… abandoned.

And there we have it, folks—the primary attachment trauma. And with that, one of the oldest routines in my nervous system came online. Because, for me, enduring this chaotic inconsistency in affection, attention, and care is so bloody foundational. It’s the reason every EMDR session I do comes down to the same core suite of memories. Why I am who I am: I was emotionally abandoned by my parents. I felt no real safety with them; worse, I felt decidedly unsafe, alone, and unloved. I managed the best I could with a whole host of brilliant dissociative and self-soothing behaviors.

Goddamn attachment injury. Cursed trauma response. Fucking limerence. I saved myself as a child, and son-of-a-bitch, I would save myself now.

John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shalott (1888).

Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.

So, once again, I find a name for an insane and awful way the neglect and abuse of my childhood has press-ganged my brain into some off-the-wall, totally bizarre survival strategy. And, surprise, surprise, I am deeply ashamed of it because, until that text exchange with a friend, I would never have had the perspective to stop believing that this was all just me being weak-willed and foolish.

After getting over my initial chagrin—after I had time to read, explore, process, write, and all of it—I found myself rather amazed. Despite our uniqueness, varied histories, and random circumstances, we still function and malfunction in similar enough ways that books can be written and classes can be taught about psychology as a science. But mostly, I am just always blown away that, given everything, we still all break in roughly the same ways. We rarely acknowledge it, though, because we often prefer not to discuss it. When, in a later conversation, I thanked Brad for bringing the concept of limerence to my attention, he quickly countered with, “I am sorry.” That apology, I assume, was offered because most people don’t love being made aware of yet another way their early wounds and relational trauma have fucked them up, especially in a way that can feel so dysfunctional while dragging such embarrassment and stigma behind it. Who wants to admit they suffer from limerence, for fuck’s sake?

Well, me apparently. It’s just my MO at this point. When I uncover the knowledge that had not yet been available to me, when I can name a thing, when I see the patterns, when I can trace something to a source, when I can see how a trait or behavior might have actually been serving—maybe even rescuing—a younger version of me and finally, when I can excavate the shame that has cloaked the brilliance of that strategy; when all of that is done, something usually cracks open in my heart. Something heals. Or at least, I find some honest-to-goodness acceptance.

It’s a cruelty that, as adults, we tend to feel mortified for the ways our child selves survived trauma. Not the first time my neurotype and trauma have lined up to produce a tactic that—like freeze and fawn—I am deeply ashamed of, instead of recognizing the sophistication and wisdom in the adaptation. When I wrote about fawning, my essay primarily focused on the discomfort and dysregulation that fawning caused me, but there is more to it. The awareness was just under the surface the whole time, but it took me longer to see—if fawning felt like shame and ignominy to my adult self, it felt like survival to my younger self. Fawning is the wisdom of my nervous system. So are freezing and dissociation. And so is limerence.

It’s wild how locked into these patterns I can feel, but it makes a sad kind of sense. If my young—thinking age 3 and 4 here—brain/nervous system felt constantly under threat and abandoned, my urgent escape into magical thinking and fantasy would have been a fucking lifeline. Imagine a child suckling on daydreams of connection, validation, and safety like they might their own thumb while clutching their teddy, and suddenly the adult grasping for breadcrumbs and nurturing visions of bonding does not look so pitiful. They look like they are just still trying to tend a deep, core hurt with the tools at hand. For better or worse, the instinct to escape into imagined love didn’t vanish as I grew—it just grew up with me.

These things can feel so maladaptive to me now, but without them… I don’t even know. How would a three or four-year-old version of me manage if she could not please and appease, self-soothe, fantasize, and escape? I won’t be histrionic and say that I might not have survived, but things might have been even uglier, harder, and more unkind, and that is a staggering thought. It’s still difficult for me to fully accept this, but things might have been much worse if I had not coped in these ingenious ways.

John William Waterhouse, Tristan and Isolde with the Potion (1916).

Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.

I have seen a lot of writing pondering why some people are more likely than others to experience limerence. There is clear messaging about why and which attachment styles are most often associated with this propensity (disorganized for the win!). There is even chatter about how neurodivergent folks are more prone to limerence than neurotypical folks. There is certainly acknowledgment that limerence is fueled by our nervous system and neurochemicals. Nothing as of yet, I think, linking limerence to the default mode network. That’s just an intuition on my part.

All of this conjecture tracks, at least for me. My primary attachment injury and the ongoing neglect and emotional abuse in my home required a robust toolkit of dissociative tactics. The specific methods I honed were informed by the weaknesses and strengths of my neurotype. Compensatory fantasy became my go-to. Even now, my autistic mind loves to plan, script, and review both real-life situations and invented ones. My dyslexic brain excels at storytelling, and my ADHD brain craves the neurochemicals that come with hyperfixating on daydreams and parasocial stories of safety and love. I can do all of these things so efficiently. It makes limerence as easy for me as drawing breath.

Oh, the things we will do when we are hurt! The lengths we will go to save ourselves are nothing short of amazing. Such brilliant, awful, strategic, haphazard tactics. Every inch of ease covers a landslide of loss. It’s all care at a cost. Self-soothing with food, drugs, sex, and whatever else is not morally problematic so much as it is just distancing from or covering up the real wound. Compensatory fantasy becomes maladaptive daydreaming when you spend more time in, and remember more about, your fictional life than you do your real life. Limerence is distracting, head-spinning, and heart-wrenching even as it bathes your brain in feel-good chemicals. Avoidance is like that, too. I have to face the reality that just because I did my best to escape intimacy for most of my adult life, it does not mean that I was actually healing the wounds that caused that behavior in the first place. I was distancing myself from them.

Recently, I found myself in a place where I am interested in intimacy and less fearful of vulnerability. Huzzah. I see now, though, that my body, brain, and nervous system remembered well how to deal with the uncertainty and unpredictability of faltering affections and attention. The more tentative and confusing the connection, the clearer the need for safety and the more obvious and high-octane the response. The inclination and propensity had been there the whole time, just itching for the perfect romantic predicament to kick it all into high gear.

Disengaging from limerence feels like withdrawing from a drug. It requires self-awareness, mindfulness, and even self-binding. Getting a grip on it is so frustrating, and it’s hard to hold yourself with kindness instead of beating yourself up. Ultimately, it requires facing the old wounds that created the patterns in the first place. I am nowhere near done with that task, but I can at least say I have eased my infatuated heart with the knowledge that I can mind and protect myself. I can work on forming secure attachment with myself, and while that lacks the relational work I am so eager to do, it’s not nothing.

When my first limerent object stomped on my 20-year-old heart, I wasn’t able to understand that everything I was experiencing had more to do with me than it did with him. He was the antagonist in a blistering tale of jilted love, loss, and longing. I was a lesser character. I’ve carried that narrative with me, and while that disaster of a boy stopped living rent-free in my head ages ago, I don’t know if I ever really forgave my younger self for falling for him, trailing after him, and yearning for him for such a long, long time. Knowing what I know now about my trauma, neurotype, and limerence, I feel like I owe that part of me a sincere apology.

Making slow progress with my heart, brain, and nervous system here, folks.

It took a few weeks of unchecked reeling, followed by flustered orientation, but this second go at limerence doesn’t feel anything like it did decades ago. It’s a loving message calling me back to myself—a different story of newfound awareness and acceptance, with me as the protagonist.

I can see why I responded the way I did to this lovely, inconstant man, and rather than feeling humiliation, I can offer myself tenderness and respect. I can also release the power that the idea of him had over me. This version of the tale is not about how someone else treated me unkindly. It’s about finding agency, healing, and becoming closer to the version of myself that was promised before a childhood of abuse and neglect.

I’ll take it. Gladly so—and not for the first time, and maybe not for the last—I’ll thank the universe for lessons masquerading as riveting electricians.

-mp

NOTES ON THE ART: All paintings by John William Waterhouse (1849-1917)

Public domain images via Wikimedia Commons.

Tristan and Isolde with the Potion (1916)

They didn’t fall in love; they became each other’s limerent objects. It’s meaningful to me now to look back and realize that this was the love story I chose to become obsessed with. I hated Lancelot and Guinevere; I thought they were terrible for choosing to betray Arthur. Not so with Tristan and Isolde. They had no choice. They unwittingly drank a love potion, and somehow, in my mind, this absolved them of the selfish crime of betraying Mark as they lived and died for one another. Or so I’ll keep telling myself.

Echo and Narcissus (1903)

Poor Echo.

Pining away with love for the beautiful and self-centered Narcissus. It’s certainly not the only example of limerence in classical myth, but perhaps one of the best known. And I love it especially because the self-obsessed dick who lent his name to today’s concept of narcissism plays a central role. Arguably, both Echo and Narcissus are suffering from limerence—Echo for him, and he for himself. I suppose my sympathies only go in one direction, however.

Poor Echo.

The Lady of Shalott (1888)

This lady is half sick of shadows. She lives a careful, restricted, and decidedly cursed life alone in her tower until one day she glimpses, in her mirror, a reflection of Sir Lancelot. She is transfixed, obsessed—spurred to action by her sudden, one-sided longing for him. Trouble is, looking away from the mirror and stepping away from her loom means she must face the curse that’s held her in stasis for so long, and, well, it ends her. She is determined to reach Camelot, but the curse will have none of that; she perishes in her boat before she reaches the kingdom.

Leave a Reply