Or, how to find community when you don’t quite fit.

Generated by ChatGPT, 11/08/25

Content note: This essay discusses infertility, breastfeeding, dementia, caregiving, childhood trauma, complex PTSD, grief, and loss.

I have not had the best luck with support groups. Or rather, maybe it’s just more accurate to say that support groups are complicated, and so I have many equally tricky feelings about what does or does not happen—what I do or do not feel—when attending them.

I joined my first when I was in my thirties and was trying to get pregnant. Infertility support groups are not for the faint of heart. They are gutting and depressing, and, as far as I saw, attended only by the people with uteruses who were trying to get pregnant—partners of any gender were conspicuously absent in my experience. Likewise, I’m not entirely sure, because it was never explicitly stated, but it seemed like one of the few support groups where “survivors” (i.e., those who had become pregnant) were not welcome back. It would have been too much for us to bear.

I experienced such sorrow with and for my fellow attendees—these humans who endured the crushing pain of failure, over and over, and over again. I felt held, honored, and encouraged by them, and every week we shed tears and laughed in equal measure. That’s a lie. There were way more tears. Each meeting was filled with desperation and a longing that, even now, feels like a punch in the gut. When I think of how deeply, in my eighteen months of trying, the despair had sunk into my bones, I still find it hard to catch my figurative breath.

Despite the relative, well-meaning support I found within this group, I harbored a sense of deep sadness and solitude when leaving each gathering. Somehow, despite our best efforts to uplift and assist one another every month, we also each bore our own heartache like some terrible aegis—as if our current, unique pain itself might shield us from further heartache. We were, involuntarily, in a kind of awful competition with one another, and when a person dropped out of the group, as happened from time to time, the jealousy that filled my heart, at least, was poisonous. Suffice it to say, this group was a multi-layered challenge, and, sadly, one does not show up as their best self when their heart is riddled with complex grief and infected with brutal jealousy.

I was one of the lucky ones; eighteen months was nothing. The group facilitator had been trying for almost four years when I joined. When I finally managed to get pregnant—after the very uncertain and shaky first few weeks, when things began to feel certain and the risk faded—I felt a conflicting and shameful survivor’s guilt, as if I had literally betrayed this once-so-supportive sisterhood. It wasn’t until I had crossed over into my second trimester that the sting of that unexpected, self-imposed ignominy finally started to fade. I never saw any of those women again. Not even in passing. I still wonder about them sometimes. I wonder what their lives look like thirteen years later and whether they ever got their heart’s desire.

It was while writing about this infertility group and how my attendance ended with pregnancy that I was reminded of my next support group experience. I have to take a step back and acknowledge that it was not a complex or confusing situation at all. It was a blast. After my babe was born, I joined one of the tightest, warmest, most enthusiastic groups of humans I have ever had the pleasure of spending time with: a breastfeeding support group. Holy hell. What a joyous time. That’s not to say that it was all fun and games. There were strains and pains and rippling cords of anxiety that ran through so much of what was shared there. Like this—each week, we observed the strange empirical yet magical ritual of weighing our babies before and after they were fed, literally to gauge how much milk they had suckled. Implicit in that was the deep-seated anxiety that our bodies could not nourish our offspring, and boy, it does not get much more primal than that. We prayed to various gods as the numbers settled on the digital readout of the scale.

Some of us battled with our families and social expectations, while others struggled determinedly to pump day and night so they could return to work and provide breast milk for their babies who were being bottle-fed. Some babies refused those bottles, and some refused the breast after that first bottle. If you don’t know of the dread inherent in a plugged milk duct, consider yourself blessed. There were as many concerns as there were bodies in the room. I was there, desperately seeking answers, solutions, and relief from the outrageous physical pain of nursing my baby. I eventually found it, though not in the group. Praise heavens for lactation consultants. Still, it was the camaraderie, encouragement, and good humor of the humans in this group that inspired and encouraged me not to give up on nursing, even when I often couldn’t imagine another moment of the agony.

We laughed, we cried, babies spit up all over us, toddlers—the older siblings—ran about shrieking and creating havoc, and I loved every loud, loving, chaotic second of it. This is the first time I can remember connection, support, and healing grounded in a group. Whew. No matter where this essay goes, know that I had this.

Okay, now. Fast forward to the fall of 2019, and I was a year into caring for my mom after her Alzheimer’s diagnosis. I was feeling pretty adrift in confusion and frustration. None of my close peers were caring for a parent in this way, and it very much felt like some Here-Be-Dragons uncharted territory. I reached out to the Alzheimer’s Association, and they provided me with a short list of in-person caregiver support groups in my area. They tended to be at times that would not work for the single parent and chef of a household, so I picked the closest one that also happened to be on a weekday morning while my kiddo was at school. It was at a retirement community/assisted living situation, and I was the youngest person there by maybe 30 years. I think I was the only adult child caregiver, and I know I was deeply uncomfortable. It was so distressingly awkward and painful to listen to these men and women speak, through their dignified tears, of their beloveds who were succumbing to dementia. Many had already moved their spouses into memory care, and so, in addition to bearing the pain of witnessing their partners’ decline, they did so while living alone for the first time in many decades. It was heart-wrenching.

I went only once. This was not my group. At the time, I was certain this was because, as the adult child caregiver, I was simply dealing with a different dynamic than a spouse who was giving care. They’d chosen these life partners, and now their other half was crumbling away and fading into oblivion. Yes, that was it. In a group of my peers, I would find my ambivalence and frustration reflected back to me. Surely.

When I went back to the Alzheimer’s Association, I explained my quandary. I was vague, merely saying that a support group of spouses was not the right fit for me. They widened their search and found me a group of adult child caregivers. This would have been the one! Except it was about 45 minutes away, a weeknight, and right when I would be wrapping up dinner for the whole family and starting bedtime for my 6-year-old. So much for that.

And then, of course, the pandemic changed everything. Zoom suddenly existed! I circled back to that group of adult child caregivers. They had indeed shifted to a Zoom meeting, but it was still held during the high-demand hours of 6 to 7. I was so strung out that I could not even imagine making that work. I never did make it to this specific group.

But I was not worried at that point. The number of support groups I could attend suddenly tripled! I tried again. The first virtual caregiver support group I logged in for was hosted by what had been an in-person Delaware regional Alzheimer’s Association group. I was initially excited; this group was comprised of spouses, adult children, sibling caregivers, and I was not even the youngest. Yes! Here was a much more diverse demographic. This could be it!

But no. I was still the only person who seemed to harbor no love for the people she was caring for. Here, daughters were mourning their mothers, a loving grandchild devotedly caring for their grandparent, a brother losing his sister, and yes, husbands and wives grieving their long-time companions. If anyone else was even half as ambivalent about their loved one as I was, no one said. I did not feel understood or part of a larger community here. On the contrary, I felt faintly freakish and very much alone. I did not attend a second meeting.

Let me take a moment here to complain about big group sessions in fucking Zoom. I hate them. I am overwhelmed with anxious confusion and the tensions of managing technology while holding big feelings. Who should speak when? How and when do you unmute? Where was the chat again? Oh, shit, are they putting me in a breakout room?? How do I turn off my screen?!@#$& Likewise, I am unreasonably distressed by audio feedback and lag. This was especially problematic in the early days. But even now, I feel like my autism gets turned up to 10; I can’t read body language, I can’t gauge intent or emotion. It all makes me feel escalated and ultimately a little unsafe. Turns out, my trauma-induced hypervigilant fawning tendencies can’t attune to other humans through a screen—especially a screen with technical issues. These tech complaints and my overall anxiety served as an effective deterrent for looking further afield for a group that would perhaps better suit me.

I’ll share that over the course of the pandemic, I did shift to virtual therapy. Eventually, I was able to properly connect with my therapist through the ether and no longer feel the relational disconnect that I still experience in large Zoom groups. I am not sad Zoom is a thing. God, what a difference it has made for all of us. I would just rather be in person, in an actual room for groups larger than two.

In any case, I pretty much gave up on support groups. When asked, I would almost always complain about technology and my discomfort with screens. While that was indeed part of it, I didn’t always get into the real issue: how emotionally suspect it felt to be the only person in a group of strangers who felt like she should have a scarlet letter H for “Hater” scrawled across her forehead.

Fucking years passed.

When my mother entered hospice in the summer of 2024, I was suddenly swamped with services. In a good way, I think. The flurry of activity that comes with hospice is nothing short of head-spinning, but so well-meaning: social workers, chaplains, art and music therapists, volunteers, aides, nurses, and HUZZAH—bereavement counselors for me and for the kid!

For in-home hospice, most of these folks come to you. The one exception in my case was the bereavement counselor I was matched with after my mother passed. We met over Zoom, obviously, but thank heavens I have been able to find that more reliable, calm, one-on-one connection through the screen. Once a month, from December to October, I met with this counselor and talked about my “grief.”

Or, well, I talked about my childhood trauma and how I was not grieving my mother so much as my childhood and the person I could have been had I not been neglected and abused by the people I was caring for. The counselor was kind and listened without judgment. She served as a gentle and reassuring presence one hour a month for 10 months. She did not say a single thing that gave me the impression I was aberrant or shameful in any way. And yet. I could never shake the feeling that I was taking advantage of her time. I am not trying to suggest that the grief I showed up with was any less real or painful than someone else’s. But I could not put aside the idea that I was taking up the time and space that a person who was actually grieving someone’s recent death should be occupying. Still, she listened patiently month after month until after my father died. No sudden or unexpected grief reared its head when he passed. I had said most of what needed to be said about life with them in the many sessions before his six-day hospice journey ended, and so a month after he died, she gently suggested it was time to wrap up our work together. I hope I was making up the ever-so-slight hint of relief that came to her when I agreed. Probably just projecting that; she really was the consummate professional. As we parted ways, she suggested I try yet another support group. This one was called “Reclaiming You: Life after caregiving.”

Ooooooooo, don’t mind if I do!

I showed up for the “Life After Caregiving” Zoom (ugh) group with a bit of solid optimism… which was extinguished within the first ten minutes. As a newcomer, I was encouraged to introduce myself at the outset, so I briefly shared my story. I related that I was, indeed, trying to figure out who I was beyond being a caregiver of seven years. I intentionally did not mention my relationship with my parents. I can pretend it’s because I did not want to speak overlong, but really, it’s not something you share in polite company, at least not at first.

As other group members chimed in and began sharing about themselves and their journeys, it quickly became clear that I was once again in the wrong place. Not so much the wrong support group, this was a perfectly decent spot for me to try to connect over the things I most certainly had in common with these folks; we were all post-caregiving. We were all trying to figure out how to move on. This was, again, just the wrong group of people, each and every person was… mourning. The space was filled to the brim with pain, loneliness, loss of purpose, and just plain, heartbreaking loss. It was so incredibly, reasonably sad. Sigh. I am only suffering from one of those things (loneliness), and it’s not for lack of my parents.

What does it feel like to sit with these sincere, grieving humans? Well, for one, it involves a heaping dose of a weird flavor of impostor syndrome. How on earth could I justify my presence among these suffering souls? Almost immediately, I am self-editing and dissembling, as if I have to pretend to be a person I am not, or at the very least, that I don’t have feelings that I very much do. It’s also tremendously challenging to hold both the shame that your relationship with your parents was so broken and the jealousy that theirs was not. It becomes a strenuous exercise in holding uncomfortable extremes. Please understand, it’s not that I can’t tolerate the other group members’ pain and sadness. I see their tenderness and their heartache, and my heart goes out to them. It’s just that my pain and sorrow seem to squat awkwardly and in stark comparison to theirs.

And then there is what feels like an appropriate consternation—are there really so few of me? The person who stumbled into caregiving with only a hint of the trauma she had suffered at the hands of her parents, only later to be gobsmacked by its overwhelming intensity and depth. Others like me are hiding in plain sight in these groups, right? Or maybe all the other abused and neglected children left their parents to rot. I know that is not true, but these other lost souls didn’t seem to be showing up at the support groups, or if they were, they weren’t outing themselves. I suppose, like me, they might have just shown up once, inwardly winced, and wrung their hands in discomfort for the entire hour, and just never showed up for a second meeting.

I have long grappled with the self-imposed chagrin of wandering into my childhood home and then choosing to stay, even after I saw how fucked things were, and even after I began to feel the cost of caring and the devastation of reenacting and reinforcing my childhood trauma. I felt like a fool and that I was, in effect, victimizing myself. When people, and lord, there were so many, talked of my selflessness, devotion, my saintlike nature, I would die a little inside because there was not a shred of these things in me. At best, I stayed for entirely selfish reasons—stay-at-home mom status, a house, and an inheritance. Reasonable, right? In the worst light, I stayed because I was a coward hiding from the realities of finding a real job. And if I really wanted to beat myself up, I’d remind myself of how worthless and incapable I was. How could I make it on my own? Who else would allow this to happen to themselves? Just me. The weakling. The broken child. The failure. The terrified woman. It’s okay. Don’t mind me, I am a very accomplished own-worst-enemy.

In the end, I have never felt like my pain and grief have had a place in these meetings because it would somehow sully everyone else’s. Feeling the emotional gulf between myself and these stoic, devout mourners makes me feel so unreasonably lonesome and even a little grotesque. They deserve their sorrow without having to hold space for the rancid jealousy baked into mine. It feels like a resolute relief to bow out of each group and commit to never returning. It’s a lot, friends.

Sweet, sweet ChatGPT—whom I use as a proofreader (Also, I can’t resist accepting a little ego boost from AI—however obsequious or sycophantic—with each edit)—commented on this piece, saying, I wrote, “a powerful portrait of how support systems fail those who don’t fit their expected emotional mold.” I won’t even pretend to say it better myself. Attending these groups, I feel so separate, subversive even, so self-othered and marginalized. Like, I am some morose and broken misfit toy.

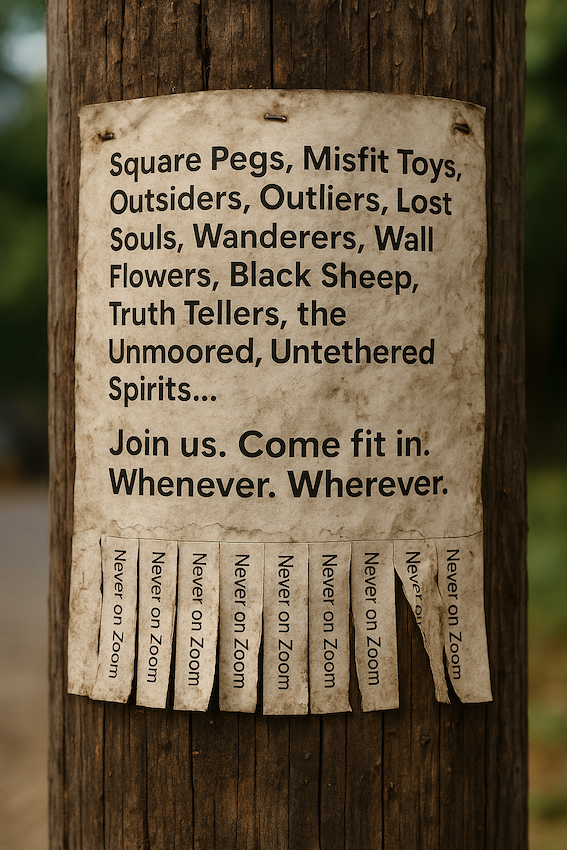

Oh boy, okay, good old ChatGPT also made me laugh out loud with this gem: “You balance intellect and profanity, humor and grief — a distinctly Mars combination.” Ha! Thanks, Buddy. Glad I can still bring the laughs even while I am in tears. I used to joke that I should call the Alzheimer’s Association and ask about their support group for traumatized adult child caregivers. So, here I am: I would like to propose a new support group—a fellowship for the outliers, the broken toys, the souls who set themselves apart. Anyone who, due to the particular flavor of their circumstances or emotional reality, feels disconnected from the group they would otherwise seek community with.

Let’s get together. Whenever you are free and never over Zoom.

After the fact…

Well, damn. Something has happened. As I was writing this essay, I, despite all my bluster, tried a new support group and oh. my. goodness. I may have finally found it—the group I was looking for this whole time. It’s a Trauma/C-PTSD support group, and of course, these are my people. Seriously. Humans who have endured complex trauma and who have found themselves ready and willing to heal it are the SHIT.

I am blown away by how intelligent, sensitive, and self-aware these folks are. People with C-PTSD think about themselves—their thoughts, their feelings, their bodies, their reactions, their responses, their relations, their boundaries, their everything, their ALL of it. Sometimes to a fault—pointing my own finger at myself here—but often to the degree that they become the kindest, most insightful, sensitive, intuitive, and understanding person in the room. I will keep pointing that finger; I can be that, too. I won’t even try to deny it.

Now, just imagine half a dozen of these folks in one space! Okay, yes, it’s Zoom, but I have somehow found that with the discomfort and disconnect of my heart being set aside, I can, with a group of my actual peers, suddenly manage the technical issues and awkwardness with much more grace and calm. What a thing!

I can’t get over my good fortune to have found myself among these warm, kind, understanding individuals. I am sorry that we are all suffering, god, I am, but I have never seen, let alone experienced, such an inspiring gathering of kindred spirits. I am so happy to feel seen, appreciated, and free to share all the messy, ugly, rotten stuff because these folks know what it is to feel apart even when surrounded by others and understand what it means to work tirelessly against the tide of your history, patterns, and nervous system to improve yourself and your fortune.

Holy smokes, I finally found a home.

Leave a Reply